So far I've been arguing how the "morality institution" arose as a specifically Protestant construction, referring to the residue of divine laws which bound all humanity as opposed to the ceremonial and civil laws of Israel. And then how this "morality" became an autonomous institution today which we should question and interrogate.

In this post I want to posit an alternative way to understanding biblical rigtheousness and divine law apart from the morality institution, and that is expectations which based on divine revelation. But a few preliminary philosophical remarks are necessary.

Ought and Should Language

Even variants of moral nihilism do not and would not reject ought and should language tout court. For example, there would be a valid place for such language in instrumentalist means-ends reasoning, e.g. you should take this route to get to your destination in the shortest time, you should use more rye for a denser bread. But in these examples the "ought" or "should" are based on positive facts about how certain actions will enable one to achieve one's objectives. Thus, "You ought to do x to get y" really can be reduced to "If you x you will get y". What the moral nihilist would reject is the idea of a moral irreductible sense of oughtness or obligation as sui generis ultimate and foundational.

The task of this post as such will be to account for the "ought" and "should" language, which traces it back to specific acts or revelations of God, which doesn't just leave it "hanging" as it were autonomously in the air. Bascially to reduce ought and should language to positive claims about God.

Morally Binding God and the Morality Institution

Bernard Williams's critique of the "morality institution", which I've read many moons ago, still remains to my mind the most incisive breakdown of the morality institution and all its problems. It's very hard to unsee the artificial nature of the construction of the morality institution once one reads Williams's breakdown. I don't intend to rehearse his arguments in Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, and I would refer you to this Stanford Philosophy Encyclopaedia page for a superb writeup and summary of his arguments.

I do however one to focus on one feature of the morality institution and that is "the obligation out-obligation in principle". This principle is the idea that every particular obligation needs to be justified by a general moral obligation. Thus, person y can only have an obligation to keep his promise in x circumstances if there is a general obligation for everyone to keep his promises in all instances. Thus, there is a push towards universalisation and generalisation.

It is obvious how this will lead to the idea of God being "subordinate" to moral laws. If there is an obligation for God to keep his covenants, then this obligation which God is under is subject to a general obligation to keep covenants in general, of which God's obligation is but one instance of a general obligation. The problem is not ameliorated by the consideration that promise keeping just is part of God's character as that would simply be divinising and turning the characteristic of promise keeping itself into a god which can compel God, especially if one believes in something like a strong doctrine of divine simplicity where every characteristic or property of God is God himself. Thus, there is God, and then there is a sort of Platonic Form of the Good or Just which inserts itself into God and compels God to keep promises.

The task of this post as such is to not let us jump out of God and His revelation, as it were, to whatever abstractions like moral laws, properties, or characteristics which compels God to keep his promises.

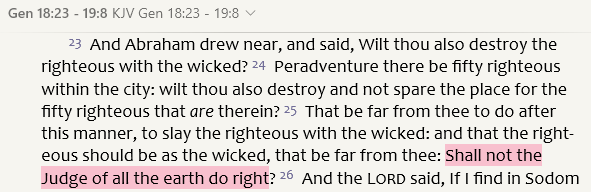

"Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?"

We are familiar with the above passage where Abraham repeatedly "bargains" with God to spare Sodom and Gomorrah with fewer and fewer righteous persons in their midsts. But notice Abraham does not "prescribe" to God what He ought or ought not to do, as if God were obliged, but rather, he raises the expectation he holds that "shall not the Judge of all the earth do right".

I suggest as such these two verses as the foundation of divine rigtheousness.:

Psalms 62:5:

My soul, wait thou only upon God;

for my expectation is from him.

and

Proverbs 10:27

The hope of the righteous shall be gladness:

but the expectation of the wicked shall perish.

Thus, for my main thesis on divine righteousness:

Divine Righteousness is satisfying the hopes/expectations which men have of God based on what He has revealed to them in creation, miracle, and covenant.

First, notice that this is completely positive, there is no normative should-ought language here. Second, this thesis is carefully qualified to hopes and expectations based on, or derived from, what God has actually revealed. Thus, the "expectation of the wicked shall perish" because they do not base that expectation from true divine revelation but based on the imagination of their hearts and false constructs of God based on philosophical speculations of the "Form of the Good" or righteousness or whatever.

Thus there is no autonomous set of moral obligations, self-evident moral truths, platonic forms of the good or right floating anywhere which binds God or forces its way into God's nature or character. There are no obligations, the nature of divine righteousness should be understood wholly within the confines of what God has revealed to us in creation, miracle and covenant, and expectations which arise from this revelation.

I think there is something to be said for this thesis as being able to account for the Old Testament attitude towards the divine righteousness, both their anguish, hopes, and expectations. There is never the sense that God has a "moral obligation" to succor Israel, but rather, the Psalmists approach is that of an expectations based on God's covenant and prophetic revelation which they have yet to see fulfilled, their own frustruation that their hopes and expectations have yet to be realised, and then their faith that nevertheless God will honour and fulfill the covenant. Thus, divine righteousness is basically the satisfaction of such hopes and expectations based on God's revelation.

UItimately if asked, but why ought God or why should God honour his covenant, the answer has to be nothing obliges God, there is no ought or should about it. It's whether you believe that God will or shall honour his covenants or you don't. It's simply a matter of faith, not deduction from more general foundational principles. As God himself says, he can swear by no one higher than Himself. He either proves Himself to be a God who honours his covenants or not, and to evidence his faithfulness, all we have is the historical testimony of God's past faithfulness to Israel and the church.

Thus, the residue truth of the "righteousness is a divine property" thesis is that God honouring his covenants is just what He does and what He has done throughout salvation history. But this has to be relativised to expectations which arise only from what God has revealed to us in miracle, covenant and creation, not based on our discovery of "self-evident" moral truths or axioms, and it has to be based on the history of God's past faithfulness to the divine covenants, not based on deductions of a general form of the Good or Righteousness.

Thus, the residue truth of "natural law" and, dare I even say, "moral laws" is that there is a legitimate expectation of God which arises from natural revelation or natural theology. To the extent that the natural man can rightly or truly discern what God has revealed to mankind in creation concern actions which please Him and good effects which will follow, they can have an expectation of divine righteousness based on natural revelation. But naturally the noetic effects of sin and the corruption of man's hearts means that their expectations are more often than not based on false idols and misapprehensions of divine revelation.

Conclusion: Expectations from God Himself

Thus we have a simple positivistic understanding of God's righteousness which does not appeal to morality or moral obligations: the satisfaction of our hopes and expectations derived or based on divine revelation to us in miracle, creation and covenant. From here I think we can derive the usual moral languages or oughts, but which keeps us firmly within the bounds of revealed salvation history without needing to jump out to platonic forms of mores and cutoms.