[John Milbank] borrows Hauerwas’s notion of narrative theology, which prioritises the historical experience of the Church: ‘Bible-Church constitute a single, dynamic ‘inhabited’ narrative’. And he identifies the basic narrative, or mythos, of the church as the ‘ontological priority of peace over conflict’ – an account inspired by Augustine and Girard.

Milbank’s vision raises an obvious question: what particular community is being celebrated here? In an essay replying to various critical responses to his book, Milbank acknowledges the somewhat abstract character of his ecclesiology. ‘[T]he church is first and foremost neither a programme, nor a ‘real’ society, but instead an enacted, serious fiction…’ It is not an ideal state to be arrived at but an ongoing performance, whose centre is the ever-repeated ‘gift’ of the eucharist. In an article of 1991 this ecclesiological idealism is also explicit: ‘The community is what God is like, and he is even more like the ideal, the goal of community implicit in its practices. Hence he is also unlike the community...’

Theology for Milbank is a sort of utopian sociology; it reflects on the ideal community of the church, which seems to hover somewhere between existence and non-existence.

Theo Hobson: Ecclesiological Fundamentalism

I wish in this post to analyse the different components which constitutes what we normally call the "Visible Church", and with this analysis, to work out what it means to join a particular church polity and the motivations and justifications for doing so. I would argue in particular that conversion to another denomination based on some vague narrative sense of "being part of a tradition" rests upon two questionable assumptions. The first is what I shall call the "theological trickle-down effect" whereby it is assumed that privileged ecclesiastical texts "somehow" has some impact upon the ecclesiastical corporation as a whole. The second premise is that idea that joining a church is about a matter of some myth making of being part of some narrative rather than as prudential judgements of the best way to obey the will of God.

What does it Mean to be a Member of a Particular Church Denomination?

In order for us to properly discuss what it means to join a church we shall need to analyse and break down the church into its component parts. There are basically three parts to most church denominations today.

1. Canonical Fellowship

First, most churches nowadays are constituted as a legal corporation or canonical polity. A church in this sense is a legal corporation made up of constitutions, canon laws or by-laws, trustees, directors, etc. On this conception to be a member of a particular denomination is quite simply a matter of having your name down on some parish roll or legally recognised document. The legal mechanism itself determines who is in and out of fellowship with such a church. It should be stressed however that not all churches have such a legal or canonical structure, the most obvious examples being the underground or informal Protestant fellowships or groups all over the world which are unable to attain legal incorporation for some reason or other.

2. Lived Fellowship

A church does not only consist of legal documents or having one's name on the parish roll. There is a set of lived practices which constitutes an important part of what it means to be a member of a denomination or church corporation. This criteria is a little more difficult and nebulous as it no doubt differs from denomination to denomination. However I think that most churches would generally consider being able to partake of the Lord's table, or Eucharistic sharing, to be constitutive of a lived fellowship.

Now we must be clear that this "lived fellowship" is not the same as what is commonly called "Eucharistic fellowship". Clerics may sign pieces of legal documents allowing or forbidding various groups of people from partaking of their tables. However this is simply part of the "legal structure" of the church corporation, that is, point 1. Clerics themselves who are part of such a corporation may or may not decide to follow these legal decrees. Having one's name on some legally recognised parish registrar (or not) is one thing, but whether the priest at the parish will or will not commune that person is another.

Thus we can see from here that there is no intrinsic convergence between "lived fellowship" and "canonical fellowship". Christians may partake of each other table whether or not a legal document exists authorising it. Clerics and ministers may choose to ignore their corporation's legal documents, or interpret it differently, and commune people who are so technically forbidden by such documents. (There was an amusing anecdote about Stanley Hauerwas, a Protestant, taking communion at his university's Roman Catholic chapel on a regular basis. Once when a priest refused to give him the communion he simply joined another queue!)

To summarise this criteria of church membership, one is a member of the church if one simply partakes of the life and practices of the church independently of their status in legal documents.

3. Confessional Fellowship

The Christian faith is distinctive in that it proclaims a concrete message and makes truth claims, namely the Gospel. An important, and man would say vital, part of what it means to be a member of a particular church corporation is that one believe or subscribe to the tenets taught by that church corporation. Such tenets are normally encoded into ecclesiastical or legal documents such as creeds, confessions, articles of faith, even canonical decrees. These tenets may also not be encoded in legal documents but simply become apart of the lived practice of the church, such as the liturgical recitation of the Nicene Creed or the use of the Apostle's Creed in baptism. Thus subscription or confession of such tenets encoded in various ecclesiastical documents, or liturgy or lived practice, constitutes "confessional fellowship", fellowship consisting of a shared subscription to the same religious tenets.

The Theological Trickle Down-Effect

Now that we have a much clearer idea as to the distinct components which constitutes church membership, it should be apparent at once that all three do not necessarily converge. A member of a church can subscribe to a particular tenet independently of whether it is encoded in some legal document or particularly promulgated or reinforced liturgically. One does not need to recite the Nicene Creed liturgically in order to believe its tenets. On the other hand a legal document may decree the subscription to a specific tenet but is expressedly rejected by both clerical and lay members of the legal corporation.

Consciousness of these distinctions however pose a huge problem with the idea of what it means to be a member of a particular denomination or tradition. What exactly does one mean? Literally a "tradition" simply refers to the things which are "passed down". It in itself does not speak of the medium or mode of the transmission of such things. Is it passed down by a simple legal decree? Clerics transmitting such teachings and practices to the laity and other clerics in a lived manner independently of what is legally written?

Yet from the way the phrase "being a part of a tradition" is used, it is implicitly assumed that the participation in some liturgical practice or subscription to some tenet is somehow associated with or necessitates submission to some legal corporation. But this is an absurd assumption as our foregoing discussion has pointed out. Do you mean to say that I cannot believe in theosis until I join an Eastern Orthodox ecclesiastical corporation? Or that I cannot read the <em>Summa Theologica</em> profitably, even subscribe to some of Aquinas's arguments, without submitting myself to the Bishop of Rome? Can a church not use the sursum corda until it is canonically affiliated to some other liturgical church? Does anyone seriously believe that one will have to be Eastern Orthodox in order to benefit from the insights of St Athanasius?

The reply may go that they are not suggesting anything so absurd as the claim that one will have to sing the liturgy in Russian in order to accept the insights of Fr. Georges Florovksy. However they may say something like, they want to join a church, or community, where the insights of such people are promulgated and has an effect upon the lived practice of the people.

This is what I shall call the "theological trickle down effect". It is the unexamined claim that certain writings or ecclesiastical documents, normally past ones, written by various prominent figures or encoded in various official documents, would somehow, mysteriously, have an effect upon the lived practice and belief of the church today. It should be apparent at once this theological trickle down effect is analogous to the economic "tickle down effect" whereby increasing the wealth of people at the top would have a "tickle down effect" for the poorer people at the bottom as their wealth, through some abstract mechanism, would somehow benefit the people at the bottom.

Criticisms of the "Theological Trickle Down Effect"

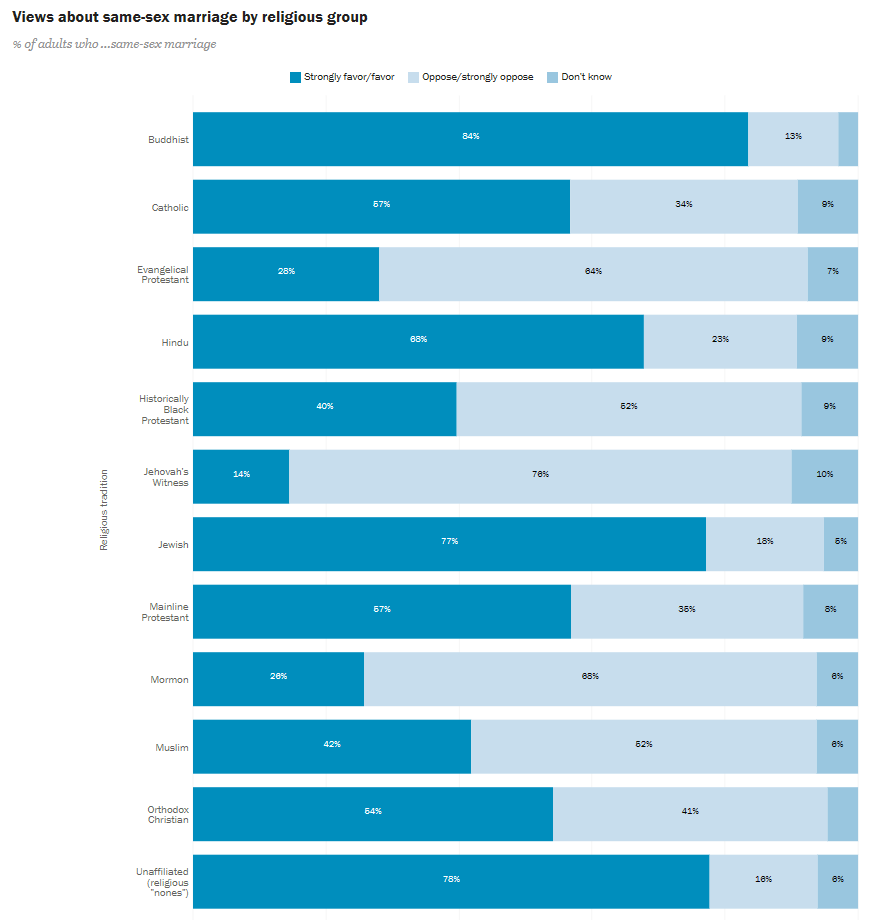

Yet, survey after survey has shown that generally there is no inherent convergence between authoritative promulgations and convictions at the top and what is believed at the bottom by the laity. There is little evidence of the theological "trickle down effect". In the below poll we can see that support for same-sex marriage among "high church" denominations like Romanism and Eastern Orthodoxy are about 57% and 54% respectively, about the same as Mainline Protestants which is about 57%. Evangelicalism, with the weakest authoritarian structures, ironically perform much better at 28%. (Jehovah's Witness is about 14%, which suggests a different thesis about the correlation between theological orthodoxy and biblical morality, but that would require a different discussion.)

Pew Research Centre: Views about Same-Sex Marriage

It should be quite virtually self-evident that there is no reason to believe that simply because something is written on some legal pieces of paper that the local clerics would enforce them. If we take the denomination with the most impressive legal machinery, the Roman Catholic Church, it should be quite obvious that the canons are rarely enforced and a plurality of divergent beliefs exists upon the clergy, never mind the laity.

If this is so for current legal documents, it is even more so for past theological writings. There is the obvious special problem of accounting for the theological trickle down effect of more difficult and esoteric theological writings of various doctors of theology or saints upon the clergy or laity, most of whom would hardly be familiar or intimate with them. If there is a problem with accounting for how the theological insights of such saints flow down from scholar to cleric and laity, then the problem of accounting for how their insights flowed down across time to our present church is even worse. On what grounds can we claim that the writings of an apostolic saint, or even a medieval saint, effected the church of today, almost centuries, if not more than a millennium later? Especially when all denominations today have morphed and changed dramatically since their time? On what basis can we say that one particular denomination has been more affected by such and such set of theological writings or works compared to another denomination?

Hermann Sasse has already long ago pointed out the problem of establishing the historical continuity of a church across time. He argues:

To provide the proof for the identity of any historical construction is always enormously problematical. One may, for example, speak of an English nation and of a German nation that continue through the centuries. But if one looks more closely, one notices how great are also the differences. In what sense are the English people of Henry VIII’s time identical with the 10 times as many English people today? In what sense are today’s German people identical with the people of Luther’s time? Was it anything more than a fiction when it was thought that the Holy Roman Empire of Byzantium was living on in the empire of Charlemagne and the German empire of Otto the Great until it expired in 1806? Is there more of an identity between the Roman Church of today and the church of Peter’s day than there is between the Roman Empire of the first century and the Holy Roman Empire around 1800? It has been observed that the difference between the church before Constantine and after Constantine is greater than the difference in the Western Church before and after the Reformation. Here the historical proofs of identity simply fail.

Apostolic Succession (Letters to Lutheran Pastors No.14 April 1956)

It is one thing to say that somehow somehow mysteriously Dante had an effect upon the Roman Catholic Church of today, but would Dante have recognised that church? Would any Roman Catholic from two centuries ago recognise the church of today? Would St Irenaeus recognise the church polity, practice or liturgy of today? Especially after the liturgical reforms of St Cyril? Would St Symeon the New Theologian recognise the Eastern Orthodox Church of today? (Or is it more likely that he would instantly start trolling the institution as he did when he was alive? Maybe he would hang out with the charismatics instead!) To echo Sasse, is it anything more than a fiction when it is claimed that somehow the church of today is recognisably continuous with the church of such and such saint? How exactly does joining some present day church corporation somehow mysteriously enable one to share in the wisdom of past theologians or saints?

It is important to note that such thinking is not restricted to converts to high church denominations. Protestant Confessionalism also believes in very strong form of the "theological trickle down effect" whereby they join some church just to be part of some "confessional tradition". Ironically, Protestant confessionalists have a much stronger claim to continuity and lived effect of their confessional tradition compared to high church denominations. After all, Protestant Confessionalists argue that their churches uphold their 16th-17th century article of faiths and liturgy, and continue to use those old catechisms and liturgy. It would be like the Roman Catholics still using the Tridentine catechism in their RCIA as well as the Tridentine Mass in all parishes. However, for reasons other than the ones considered here, Protestant Confessionalism is not a very good idea in itself.

Two Motivations for Joining a Church

There are generally two reasons for joining a particular denomination, only one of which I would argue is theologically acceptable. The first is rooted in some vague and unexamined sense of being part of some "tradition" or narrative. However this "tradition" or "narrative" did not fall out of the sky nor is it encoded in any official document. As already argued, it is simply a mish-mash of various events, documents institutional acts, and persons, clumsily glued together to give oneself the vague sense of somehow being "a part of it all" or some sense of sharing in their wisdom, insights or life. But this is, quite literally, a work of fiction. This narrative exists nowhere except in the eye of the beholder and is true of no particular lived reality, community or institution. In an unguarded moment of refreshing honesty, John Milbank, one of the main proponents of narrative theology, bluntly muses:

For all the current talk of a theology that would reflect on practice, the truth is that we remain uncertain as to where today to locate true Christian practice… . [Consequently] the theologian feels almost that the entire ecclesial task falls on his own head: in the meagre mode of reflective words he must seek to imagine what a truly practical repetition [of Christian practice] would be like. Or at least he must hope that his merely theoretical continuation of the tradition will open up a space for wider transformation.

-The Word Made Strange (1998)

To these comments Theo Hobson adds, "This is a surprisingly clear admission that his ecclesiology is very largely an exercise of the imagination." The problem with this motivation is that joining the church becomes an act divorced from God's will, rather it becomes more about some aesthetic titillation in being part of some narrative or story.

This leaves us with the other legitimate reason. We should sign up or register with a church corporation because it is the will of God. Or to put it in concrete terms, it is the means whereby we could maximise our sanctification or better obey the will of God. Against the high church adherent who would make corporate membership in some "true Church" mandated by God, unless they want to affirm that canon law is an extension of the divine will, a highly untenable claim, then there is no real theological reason to join their particular church corporation or submit oneself to their system of canon law. If they want to say that some set of their theological or ecclesiastical documents contains theological truth and that it is God's will for us to believe it, we can do so without getting our names on their parish roll as already pointed out before.

Certainly to judge the merits of joining an ecclesiastical corporation we would need to pay special attention to a church's "official" teachings, its lived practices, as well as the particular duties involved in membership. However, unless we want to commit the error of the confessionalists, we should not treat church confessions as extensions of binding divine revelation but as prudential instruments for facilitating the communication of Scripture's meaning. When we register with a denomination we may have particular temporal duties to that denomination, but we have not resigned our conscience to them. Our theology remains our own, subject to the scrutiny, judgement, and conviction of our own consciences.

In the end, the attitude of deciding a church denomination should be prudential, as means to an end, that of facilitating our obedience to the will of God, not as an extension of our "identity" or some way of spinning some all encompassing narrative for our own aesthetic titillation.

Conclusion: "Prove all things; hold fast that which is good." (1 Thessalonians 5:21)

There is no ready made all encompassing narrative, tradition or story whereby we can make sense of the entirety of our lives. We have been given the testimony of the Gospel, the natural gifts and talents of the Body of Christ, and finally our own reason which, though ravaged by sin, is not completely blind to the divine or judgements on civic affairs. There is no need for some all encompassing theological or philosophical system to make sense of everything a priori, but, believing in the providence of God, we confidently confront them, knowing that God, the Father of lights, will provide us with the wisdom necessary to engage and deal with life's many unexpected complexities.

We join a particular church corporation, not to escape the complexity of life, but to receive very particular benefits, good preaching, fellowship and liturgy. These goods can exist with or without a canonical polity, legal mechanism, confessional document or even esoteric theological tomes. Our theology is our own, our conviction is subject to our conscience alone, and we shall answer to God alone for our confession and our faith.

We are to prove all things and hold fast to that which is good. In every "tradition" or writing, we receive the good and reject the bad, believe the true and reject the false. We do not cut ourselves off from the totality of the Christian experience, no matter their age or denominational affiliation, based on some artificially contrived narrative, but are happy to glean whatever wisdom it has pleased God to bless his people with, wherever they can be found.

Ultimately, we need no narrative or tradition to be assured of Christ. For faith is a gift of God, not a work of man's narration, graciously communicated to us directly by the Holy Spirit through the proclamation of the everlasting Word. Upon this is our sure ground and we need no other to partake of the salvic life of Christ.