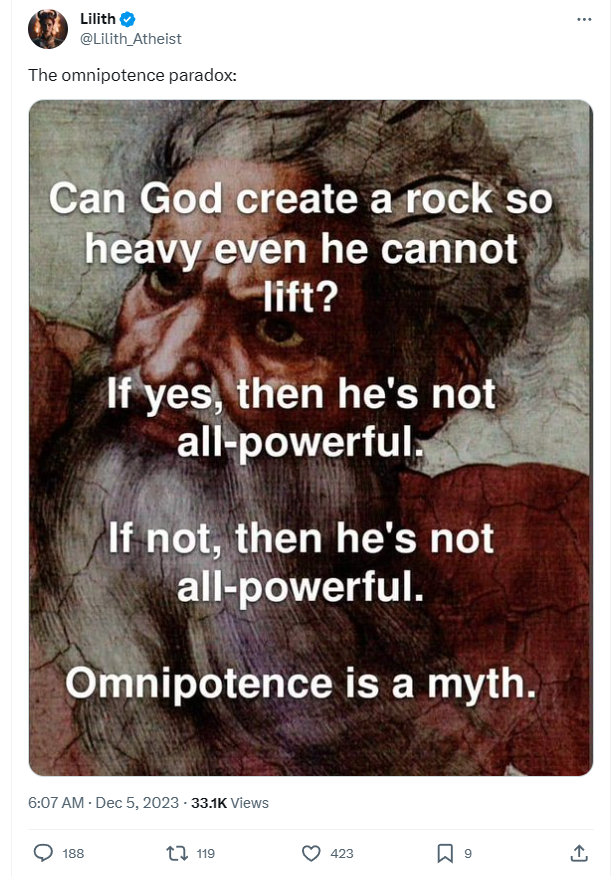

We are all familiar with this common paradox of omnipotence.

While many have responded to this paradox by keeping within the constrains of logic, there is another answer which few have considered: God can create a rock so heavy that he can't lift it, and then he can proceed to lift it, because God has the power to ordain logical contradictions.

On this point Lev Shestov in Athens and Jerusalem has some interesting remarks on the history of divine omnipotence's ability to ordain logical contradictions:

I would recall in this connection the very significant conflict, and one which the historians of philosophy for some unknown reason neglect, between Leibniz and the already deceased Descartes. In his letters Descartes several times expresses his conviction that the eternal truths do not exist from all eternity and by their own will, as their eternity would require, but that they were created by God in the same way as He created all that possesses any real or ideal being. “If I affirm,” writes Descartes, “that there cannot be a mountain without a valley, this is not because it is really impossible that it should be otherwise, but simply because God has given me a reason which cannot do other than assume the existence of a valley wherever there is a mountain.” Citing these words of Descartes, Bayle agrees that the thought which they express is remarkable, but that he, Bayle, is incapable of assimilating it; however, he does not give up the hope of someday succeeding in this. Now Leibniz, who was always so calm and balanced and who ordinarily paid such sympathetic attention to the opinions of others, was quite beside himself every time he recalled this judgment of Descartes. Descartes, who permitted himself to defend such absurdities, even though it was only in his private correspondence, aroused his indignation, as did also Bayle whom these absurdities had seduced.

Indeed, if Descartes “is right,” if the eternal truths are not autonomous but depend on the will, or, more precisely, the pleasure of the Creator, how would philosophy or what we call philosophy be possible? How would truth in general be possible? When Leibniz set out on the search for truth, he always armed himself with the principle of contradiction and the principle of sufficient reason, just as, in his own words, a captain of a ship arms himself on setting out to sea with a compass and maps. These two principles Leibniz called his invincible soldiers. But if one or the other of these principles is shaken, how is truth to be sought? There is something here about which one feels troubled and even frightened. Aristotle would certainly have declared on the matter of the Cartesian mountain without a valley that such things may be said but cannot be thought. Leibniz could have appealed to Aristotle, but this seemed to him insufficient. He needed proofs but, since after the fall of the principles of contradiction and of sufficient reason the very notion of proof or demonstrability is no longer anything but a mirage or phantom, there remained only one thing for him to do—to be indignant. Indignation, to be sure, is an argumentum ad hominem [an argument directed at the man]; it ought then to have no place in philosophy. But when it is a question of supreme goods, man is not too choosy in the matter of proof, provided only that he succeeds somehow or other in protecting himself . . .

Leibniz’s indignation, however, is not at bottom distinguished from the Kantian formulas—“reason aspires avidly,” “reason is irritated,” etc. Every time reason greatly desires something, is someone bound immediately to furnish whatever it demands? Are we really obliged to flatter all of reason’s desires and forbidden to irritate it? Should not reason, on the contrary, be forced to satisfy us and to avoid in any way arousing our irritation?

See here also for the historical development of the "Laws of Thought", that they aren't really so absolute but maybe empirically conditioned.